however, would you feel safe after a raptor attack?

adding to this uneasiness, i got an eee-mail from a disgruntled pack member who warned me i could be in bigger danger. this "ruffled feather" told me that i might be the only person who could stop the pack from profiting from their thefts, and more to the point if i didn't try they would certainly come after me...

though what they're stealing i'm not sure... which was my goal for today, try and figure out what they are after!

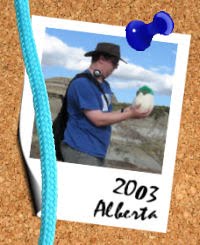

my top pick from these experts for IDing the possible fossil was dr. donald henderson, curator of dinosaurs at the tyrrell. if anyone here was going to be able to help me sort out what large unknown dinosaurs were being discovered it was dr. henderson. after all there was next to no chance something 17 meters long was NOT going to be a dinosaur!

my top pick from these experts for IDing the possible fossil was dr. donald henderson, curator of dinosaurs at the tyrrell. if anyone here was going to be able to help me sort out what large unknown dinosaurs were being discovered it was dr. henderson. after all there was next to no chance something 17 meters long was NOT going to be a dinosaur!  i hear some of you asking, "articulated, associated, and disarticulated, what does that mean?" a perfect topic for a Palaeo FACT!

i hear some of you asking, "articulated, associated, and disarticulated, what does that mean?" a perfect topic for a Palaeo FACT!

associated skeletons: again there are a lot of factors that can break a skeleton apart once the animal has died. many of these (though not all) often don't have the power to move the bones far from the body, whether this be the action of predatory scavengers tearing the body apart to eat it, or the force of water or wind that slowly pushes the bones apart from each other (typically burying them along the way).

associated skeletons: again there are a lot of factors that can break a skeleton apart once the animal has died. many of these (though not all) often don't have the power to move the bones far from the body, whether this be the action of predatory scavengers tearing the body apart to eat it, or the force of water or wind that slowly pushes the bones apart from each other (typically burying them along the way).we can find a complete associated skeleton , but it will be scattered and in need of serious reassembly. typically, associated skeletons tend to be incomplete as many bones will have been removed from the spot before burial or fossilization.

you can get parts of a skeleton "associated" with other parts of the same animal that are completely articulated . it is important to remember which is which as both articulated and associated refer to a single animal whose parts are still "together". the difference being articulated means the pieces are still together, associated simply means the pieces are all mixed up but at least in the same general area.

to be honest associated skeletons aren't ideal for any type of study. i can't think of any researcher who hopes to find associated material above articulated. though if you're into individual study (again single animal or species or genus etc.) then associated is still preferable to...

disarticulated is where the bones are not only scattered, but not necessarily from the same animal!

disarticulated is where the bones are not only scattered, but not necessarily from the same animal!

when we find a site of random bones that do not clearly belong to each other (ie. associated) one has to assume they do not come from the same animal. in some cases the bones could very likely be from the same individual animal, but due to the incompleteness or bones from another animal being mixed in you don't want to make a mistake through wishful thinking.

often disarticulated material is found in bonebeds (which you can read about it here) which are a spot in an environment in which material from many different animals build up.though disarticulated fossils might sound like a waste of time, this is only if you are interested in individual animals. if you are into studying environments or communities, disarticulated fossils, especially in bonebeds, are ideal as you can get a sample of the types of animals all living in a region.

granted it helps to have found articulated or associated skeletons of these critters before, so you know what you are looking at in a bonebed...

after looking at the poached dig sites carefully dr. henderson and i determined that the poachers had removed both pits as entire blocks, meaning that whatever fossils they took out had all been clustered together. this ruled out an associated skeleton. these tended to be spread out, and require only small chunks of rock to be taken out throughout the pit.

that left us with either an articulated skeleton or a large bonebed of disarticulated material.

i had checked around the site, and saw no evidence of any more bones. typically bonebeds tend to be much bigger then these excavation sites (sometimes kilometres wide!). moreover there wasn't much to be gained by excavating it without properly mapping it. it probably wasn't properly mapped as these digs were clearly as fast as they could be. mapping can take a lot of time to do right...

that left us with an articulated skeleton...

dr. henderson did not need any time to think of a single 17 meter long candidate to fill those quarries. the only animals that ever got to that size, that lived on land anyway, were sauropod dinosaurs.

dr. henderson did not need any time to think of a single 17 meter long candidate to fill those quarries. the only animals that ever got to that size, that lived on land anyway, were sauropod dinosaurs.

despite this obvious answer dr. hendersion was a little hesitant to accept it as the only explanation. after all there was no guarantee that they'd dug out only a single animal. for all we knew it was a site with multiple articulate skeletons together, a rarity in alberta normally.

however in face of the information i could give him, it made the most sense to dr. henderson that the poachings were of long necked dinosaurs. no sauropods were known from alberta, let alone from the drumheller region, and thus represented not only a wealth of information but probably a lot of money too. most fossil theft tends to have something to do with making money, and so finding a previously unknown dinosaur could be worth a lot potentially, especially if it is the biggest animal known from an area...

i thanked dr. henderson for his time. he'd certainly given me something to think about.

the titanosaurs, later relatives of the tyrrell's camarosaur, would carry the long necked dinosaur lineage right up to the end of the dinosaur's reign. some of the most famous and common late cretaceous titanosaurs come from the southern united states, which was not cut off from alberta by the time of drumheller's fossil record, meaning there is a slight possibility they could have been wandering around here back then.

yet no previous evidence of them in alberta had been found. studies of the environments in the united states versus those here in canada showed that long necks preferred dry highlands. texas and new mexico were a lot drier and higher in elevation then alberta 70 million years ago, which itself was a lowland swamp at that time.

it makes sense that an animal that weighed as much as a small herd of elephants would need stable footing to live day to day. the coastal floodplains of alberta certainly would not have had much of that to offer! it was nothing but swamps, lakes, and rivers, as well as large tyrannosaurids who would have loved to eat a bogged down long neck!

no, it wasn't a sauropod i thought to myself looking at the camarosaurus skeleton.

no, it wasn't a sauropod i thought to myself looking at the camarosaurus skeleton.

it made no sense... at least from the pack's point of view.

what did they have to gain from stealing the only evidence of titanosaurs in alberta? they couldn't eat it, and its not like it would have made them that much money... many of the pack members are big multi million dollar movie stars. why would they need to steal fossils to offset that kind of income?

that and the scientific evidence for albertan titanosaurs wasn't really there. just circumstantial evidence someone had dug something "big"...

no, i was going to need to look into this a little more closely.

so much for my idea of having the experts solve it for me... though i was still going to need their help.

looked like i was going to have to stick my snout into the situation after all...

to be continued...

7 comments:

That's some very, very interesting clues there. But I can't really think why the Pack would poach titanosaur fossils either.

Albertonykus- Indeed. I'm afraid I'm at a loss as well, though there's one question that bugs me: How can large theropods even dig!!! Their fore-arms weren't exactly the most dexterous (sp?)!

Traum- If you have to get involved, I, sincerely, wish you luck. Remember to watch your back!

Anywho, Nice Paleo Fact, by the way!

Oh, you're right about digging theropods, too. The only dinosaurs known to have actually been burrow diggers are zephyrosaurs (definitely not part of the Pack) and some bird species (said by Larry not to be part of the Pack). Some have speculated burrowing habits for psittacosaurids, Drinker, and even ankylosaurs, but they're clearly all ornithischians.

So, searching for answers among the Pack's potential Pack members, we can certainly rule out tyrannosauroids as diggers. Tyannosaurid tyrannosauroids clearly couldn't dig, and even basal tyrannosauroids had front claws for hunting, not digging. We run into the problem with deinonychosaurs and oviraptorosaurs: their forelimbs are great for snatching prey but not so much for major excavation. Compsognathid arms are too short, and alvarezsaurid arms, though very strong (probably good enough to pound into termite mounds and ant nests), are also too short to reach the ground.

That leaves two major groups left as potential excavators: therizinosaurs and ornithomimosaurs. It's true that some have suggested digging for therizinosaurs, and I guess that's a plausible theory for some of the small or medium-sized species. They have big claws and long enough arms. Some ground sloths (which were quite similar to therizinosaurs when it comes to ecology) are known diggers. I have doubts about ten-meter-long Therizinosaurus (with one-meter claws) digging, but Falcarius and Beipiaosaurus might manage well enough. Ornithomimosaurs were certainly runners, not burrowers, but their arms are quite long (just look at Deinocheirus!), their fingers are all the same length, and their claws are hooked like sloth claws. Major excavation work isn't for them, truth be told, but maybe they could do a little work on surface excavation.

Mind you, neither therizinosaurs nor ornithomimosaurs have had much of a mention so far. I can't help but wonder whether that's because they're on some special duty...

I couldn't help but do a bit of fan art: http://albertonykus.deviantart.com/art/Pack-of-the-Primordial-Feather-128833975

I hope it doesn't give you too many nightmares, Traumador.

Albertonykus,

Could it be that the Pack hired a Human to do the dirty work for them (Literally!)? That's what the evidence seems to point to or that there's a third party...or fourth party (if you count Traumador and Paleo Central as separate parties.)

Quite Intriguing.

That's another possibility that can't be ruled out...

I used to love the fact that most miopliocene fossils around here are articulate skeletons but .... err... after having read your post... errr... YIKES! poor animals!

Post a Comment